Tales of Tuscan Kitchens

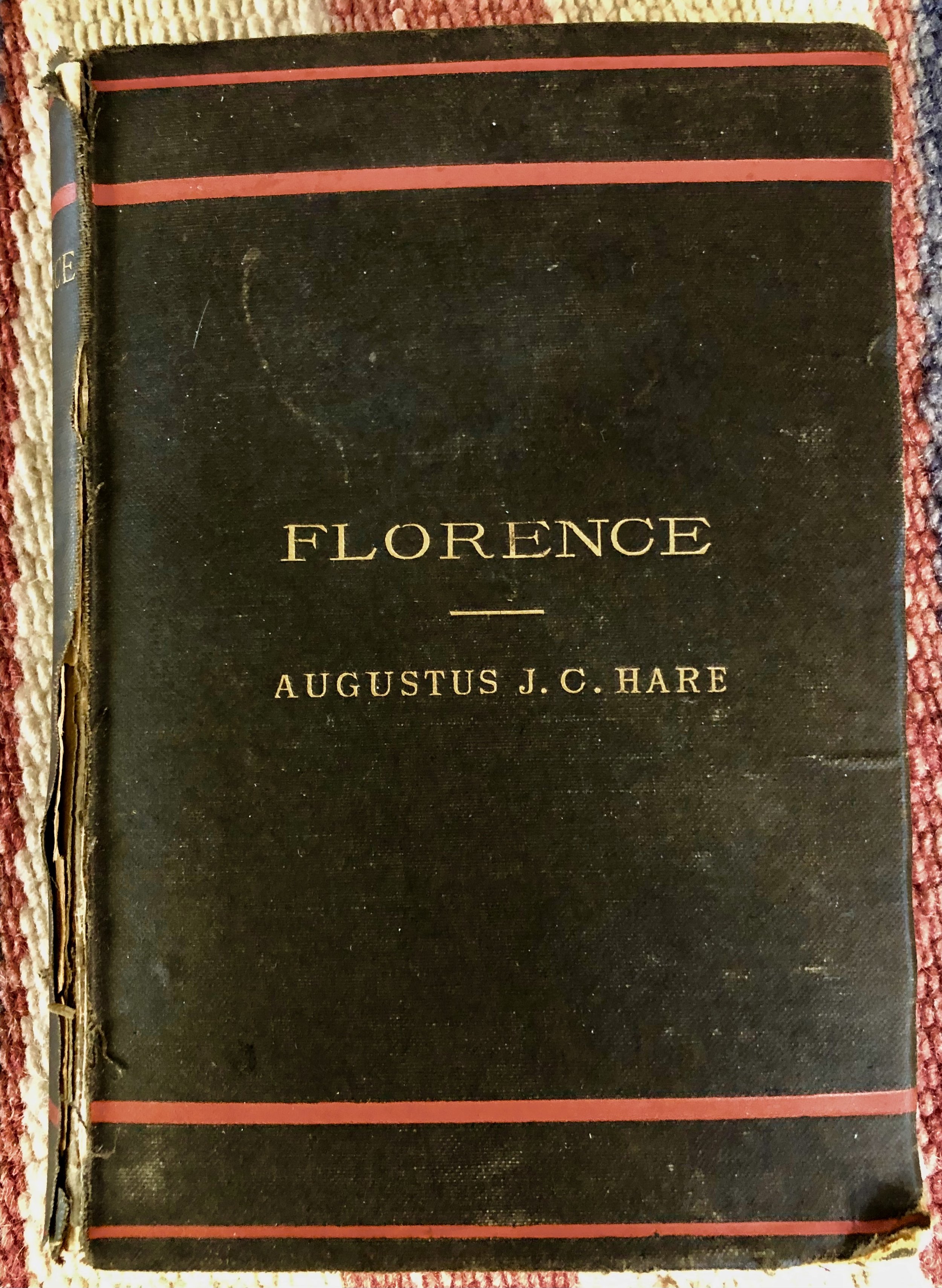

When a small elegantly bound and illustrated travel guide entitled “Florence” fell off a shelf in my studio this week, I opened it and found myself lost in memories. Written by Augustus J. C. Hare and published in London in 1896 four years before my grandmother Florence was born, it is a timeless treasure. I don’t know when Granny came into its possession, only that she kept it for decades in a drawer in her dressing table along with her hairbrushes, combs, bobby pins, powders and bottles of nail polish. I’d love to think that she had long imagined traveling to Italy to capture the light of Tuscany, just as Kit and I did on a whim a decade ago.

Our first stop on our Italian adventure was Florence, followed by a weeklong painting and writing workshop with a small group at Spannocchia—a 12th century farm estate near Siena. The first evening in Florence, we dined at La Carabaccia—a ristorante steeped in medieval Florentine ambiance. Great coal-burning grills flavored a medley of local meat specialties—thinly sliced beef, pork, and chicken—grilled and served with traditional Tuscan vegetable and pasta dishes.

Every meal during our Italian intermezzo had a story. That night in Florence, we learned that in ancient times, the “carabaccia” was a small boat in the shape of a walnut shell that transported sand and salt back and forth across the very Arno River we’d walked along earlier that day.

During the Renaissance, “carabaccia” referred to a recipe from the kitchen of the Medici family, lords of Florence. Their daughter Catarina de Medici brought the recipe to France, along with artists, artisans and Florentine cooks, when she married the second son of the King of France. Thus, she began the tradition of soupe à l’oignon, known today as French onion soup, in kitchens throughout her adopted homeland.

Our meal at La Carabaccia was a delicious introduction to what followed—a week of homemade Tuscan country meals deeply rooted in Spannocchia’s gardens and kitchen. The gardener and cook plan weekly menus, utilizing fresh produce from the estate’s certified organic gardens. Rare Tuscan breeds of black-and-white Cinta pigs, raised in the Siena region since the Middle Ages, provide pork that the cook bakes with fresh fennel, as well as sausage and aged prosciutto.

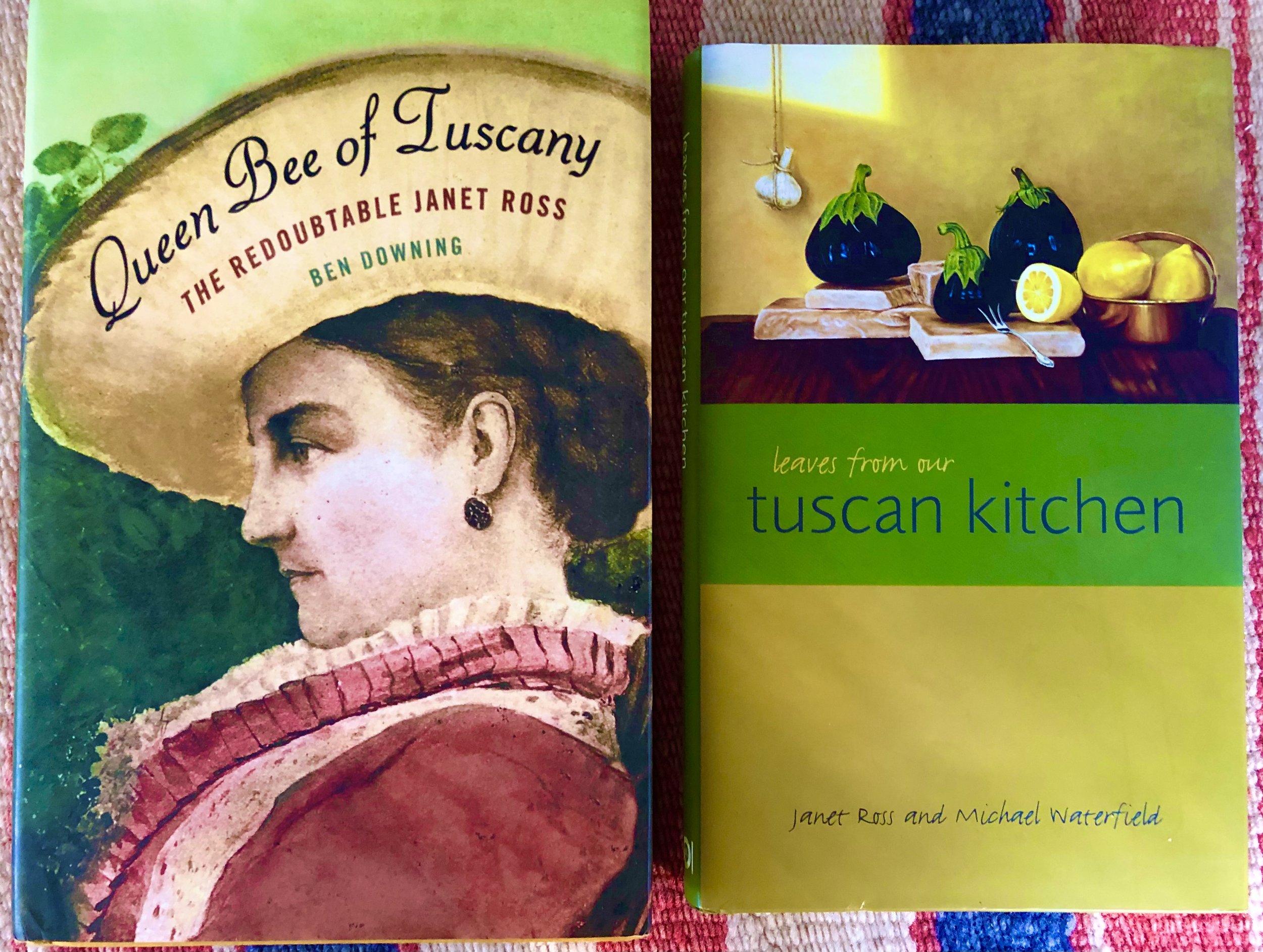

Following a morning garden tour, I joined a cooking class with Loredana—longtime cook for the Cinelli family that has owned Spannocchia since 1925. That culinary experience reminded me of English writer Janet Ross (1842-1927)—the redoubtable subject of Ben Downing’s 2013 biography “Queen Bee of Tuscany” and her own longtime cook.

Ross lived at Poggio Gherardo, a villa outside of Florence. For the last sixty years of her fascinating life, this formidable Victorian expatriate was at the literary center of Florence’s Anglo-American community. During her “reign,” Ross collected and faithfully recorded the recipes of Giuseppe Volpi—her cook for over thirty years.

This recipe collection, first published in 1899, became a classic in its own time and came to light again when republished in 1970 by Michael Waterfield, the great–great nephew of Janet Ross. In 1973, Waterfield—a chef and restaurateur himself—edited and updated his earlier edition adding a few new recipes in a 2006 edition which he called “Leaves From Our Tuscan Kitchen” by Janet Ross and Michael Waterfield.

What made Ross’s original late 19th century cookbook unique was its almost total focus on the preparation and cooking of fresh vegetables. In Tuscany, traditional meals are a vegetarian’s dream. Side dishes are never just a tiny footnote from the garden. Rather, they are a symphony of simply prepared vegetables from artichokes to zucchini—fried, baked, sautéed, served alone as a course or mixed in salads, risottos, pastas and soups.

Our dinner at La Carabaccia in Janet Ross’s adopted city of Florence had begun with Italian antipasti meats (prosciutto, genoa salame, and sopressata), followed by thinly sliced potatoes sautéed in olive oil and rosemary. The menu could just as easily have included Fritto di finocchi (fennel fritters with lemon) or Carciofi alla Francese (small, peeled artichokes boiled in water and oil and finished with lemon) from Ross’s classic 1899 cookbook.

Inspired by the serendipity of rediscovering my grandmother’s 1896 Florence travel guide, I’m now perusing “Leaves From Our Tuscan Kitchen” as well as Spannocchia’s spiral-bound collection of recipes. These days a symphony of Italian flavors and tastes are underway in our kitchen, feeding my love of cooking with recipes that speak of Tuscany.

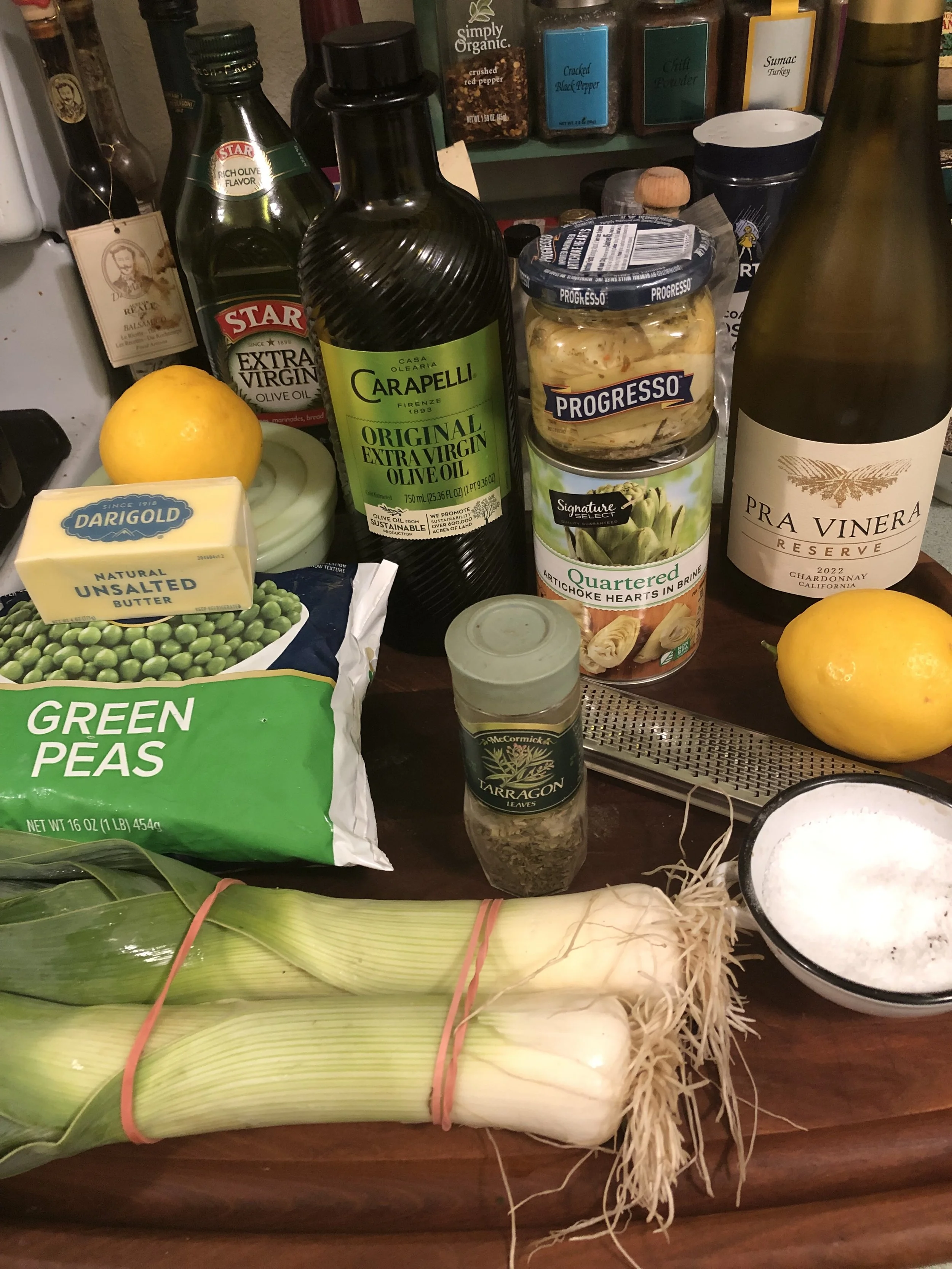

A favorite artichoke recipe this spring is from the NYTimes Cooking website—"One-Pan Creamy Artichokes and Peas” by Melissa Clark, March 27, 2024. Clark describes her creamy stew as “full of seasoned sweet leeks, lemon zest and Parmesan, and is a celebration of spring you can make all year long, thanks to the canned artichokes and frozen peas. Add a dollop of fresh ricotta and serve with crusty bread or over pasta.”

If preparing fresh artichokes this spring, visit Saveur’s website for tips and recipes — https://www.saveur.com/culture/how-to-cook-artichokes/. While steaming the green and purple globes until soft and sweet, read Pablo Neruda’s “Ode to an Artichoke”—Scale by scale/we undress/this delight/we munch/the peaceful paste/of its green heart.

Then, Buon appetito! Mangia e divertiti—eat and enjoy!