A Wing and a Prayer

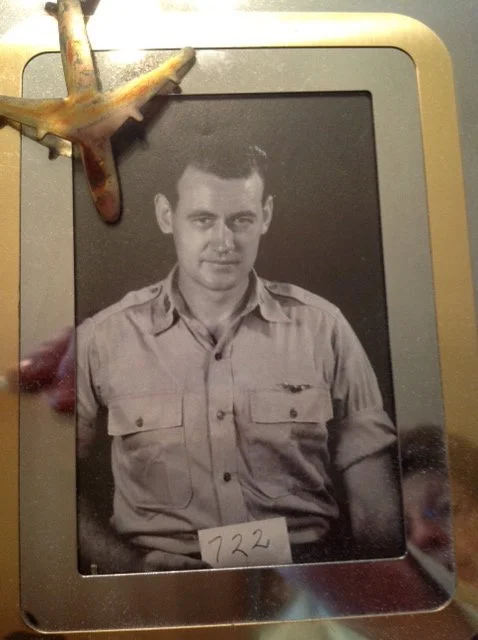

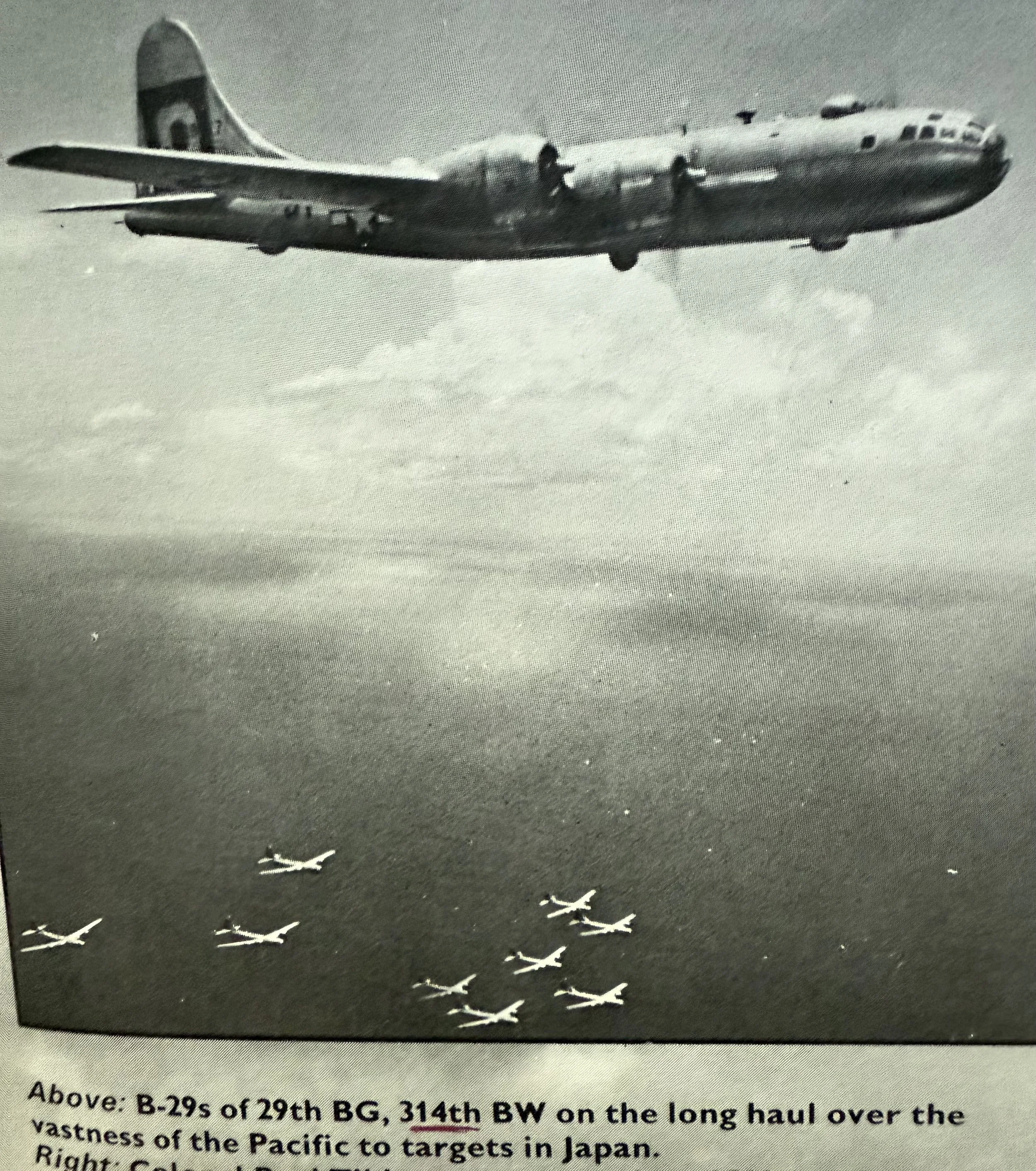

In 1945, my father William E. Riggs and the B-29 crew he commanded were attempting to return to their base in Guam after a nighttime bombing run over Japan. Their plane—a massive Superfortress bomber—and Dad’s bombardier had been badly shot up, the landing gear was gone, and they were running dangerously low on fuel. Dad was preparing the crew to bail out when a voice over the radio told them of a Japanese-built dirt runway on Iwo Jima, recently secured by the U.S. Marines and Navy. Dad executed his first-ever GCA (Ground-Controlled Approach) blind landing, floating in on a wing and a prayer safely past Mt. Suribachi—a volcano that loomed over the makeshift air strip.

Gaining access to the Navy’s mess tent proved to be more difficult. For understandable reasons, Dad’s crew did not have their Army Air Corps dress uniforms along on their bombing mission. The U.S. Navy maintained strict dress codes for the officers’ mess tent. Unable to talk their way into a hot meal, they resorted to what had carried them to safety—their own self-reliance. They took the last look at their B-29 that would never fly again, dug into their K-rations, and thanked the lucky stars they slept under that night for the new British invention called radar.

When Kit and I lived in the country in Missouri, I made a weekly run into Columbia for groceries, usually early in the morning. For some reason I’ve long forgotten, I didn’t get an early start one day. By late afternoon, the radio announcer was bemoaning the 98-degree temperatures and explaining why people should never leave pets or small children in the car in such extreme temperatures. I had noted on leaving home that the gas gauge was floating around a quarter of a tank and made a mental note to stop at our local Conoco station just down the road on my return from town.

Two hours, forty-some miles, and several bags of perishable groceries later, I passed up an opportunity for gas five miles from home. Cold air from the air conditioning system was blowing directly onto the grocery bag with the ice cream and butter, and the fuel needle was approaching but not yet at empty. Just a few more miles to our local Conoco station to go. No need to panic. Then I detected a slight pull in the engine and began to consider what I would do if I did run out of gas on Hwy 63. I had no gas can, no car phone, and it was before cell phones existed. I would have to sacrifice the ice cream, start walking to the gas station and hope to get a ride back.

That was when the bucking and pitching started in earnest. I was running out of gas. Instinctively I shut off the air conditioning and pulled off the highway. “Honey,” I could hear my father saying, “you’re out of gas. What are you going to do now?”

I sat for a few very long hot minutes, collecting my rapidly melting self-reliance, and then tried to start the engine again. Bingo! I traveled two miles closer before it failed again. Another brief stop and I made it to the top of the incline that looks directly down on the entrance to our local Conoco station. From that point on, I rolled downhill on a wing and a prayer, right into the gas station and up to an empty gas pump.

Fast forward to a week ago in Grass Valley, CA when I stopped at a grocery store before heading for lunch with Kit. Shopping done, I loaded up the groceries and backed out of my parking space. That was when I heard an ominous “whirring” noise that I’ve never heard before emerge from the engine of our trusty 2009 Toyota Rav 4. Alarmed, I took it to a body shop nearby and was told it might be aging belts that needed to be replaced.

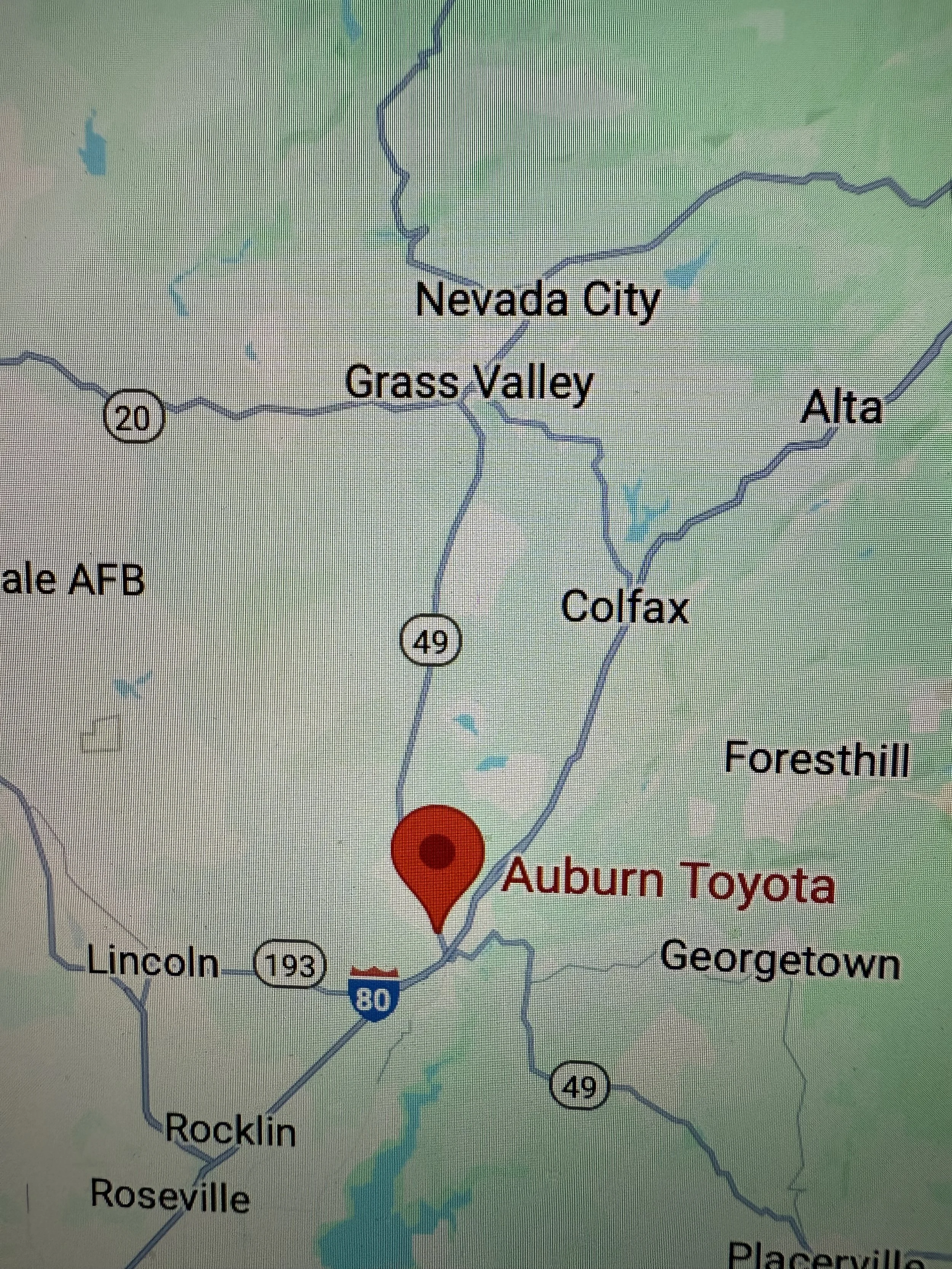

But it was Friday afternoon. No one could look at it for a couple weeks, and the Toyota dealership in Auburn that is a forty-minute drive away was booked until the following Wednesday. What to do? Early the next morning, I did what my Dad would have done. I drove my Rav 4 from our home in Nevada City to Auburn—a trip that began at an elevation of 3,750 feet and ended at 1,220 feet at the foot of the hill below the Toyota dealership.

And there I was faced with my own Mt. Suribachi challenge as I turned to head up the steep incline to Toyota’s service center. I had one stop sign and a left had turn to go before the alternator and battery gave up and died. At that moment, with my power steering gone, I was thankful that Dad had taught me to be level headed in this kind of crisis.

Like my descent on empty to the Conoco station over thirty years ago and Dad’s blind landing on Iwo Jima a few months before I was born, I made it to Auburn Toyota’s service lane that morning—on a wing and a prayer with Dad as my co-pilot.